Words by Feliks Garcia

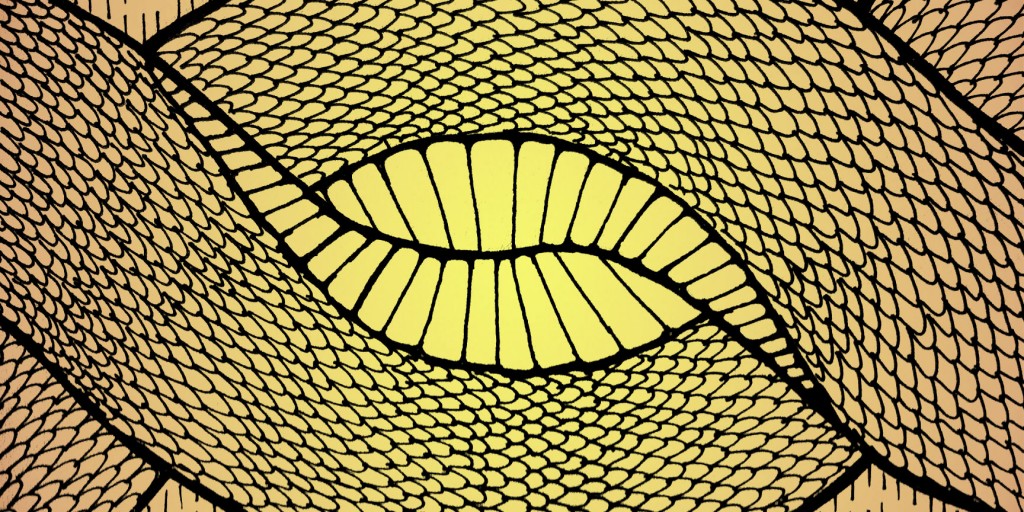

Illustration by Shea Cadrin

I took care of my uncle’s boa constrictor when I was twelve.

My uncle left the warmth of Texas for snowier climates in Minnesota and a job that was approximately ten weeks long.

I was never one of those boys who, in my adolescent years, “played outside” or “had friends,” so rarely did the opportunity to steal frogs or snakes from local ponds present itself. Instead, I was taught to fear the outdoors and all of its scaly inhabitants.

Abra, the snake (my uncle was into Satanism at the time), lived securely within a glass aquarium in the bedroom. His car was in the shop, so my mom was driving him around to take care of some errands. One of those errands involved buying mice — otherwise known as “snake food.”

At my uncle’s apartment, I was occupied with cataloging his monumental CD tower, taking record of the albums I needed to be “cool.” This uncle was the youngest of my nine uncles and seemed to have his fingers on the pulse of coolness, but never really seemed to get the whole Grunge thing. His coolness was rooted in 1980s androgyny — not the nuanced androgyny of 1970s Glam — so his fascination with Satanism had more to do with the band Dokken than the work of Aleister Crowley.

I joined my mom and uncle in his bedroom to observe The Feeding. The snake caught the scent of the frightened mouse in its tank. I stared at the snake’s scales and its rippling muscles as it circled the mouse. It quickly snapped its fangs into the mouse’s spine. The mouse’s face froze. That image is as vivid today as it was in 1995, and I can’t help but feel sad for the defenseless mouse. Yet, in retrospect, I find solace in the fact that this mouse, born in an aquarium tank, raised in captivity, met its maker by the fangs of a reptile enclosed in the same aquarium glass. The circle of life was complete. Watching that snake paralyze, crush, and swallow the mouse was imprinted in my mind.

When my uncle asked me to take care of Abra, I hesitated, then felt a twelve year-old sense of flattery that the paradigm of coolness (in 1995) would trust me with this animal. Reason escaped me, and perhaps I thought caring for the monster would convince the others — whoever they were — that I was cool. I could finally break from the shackles of boyhood, abandon little Feliks G., and roll up to my Catholic school in a motorcycle, because I was the kid who tamed the Devil, and I had the snake and Metallica records (and imaginary motorcycle) to prove it. So I said yes, then asked my mom to buy me a Metallica record.

The snake — or rather I — didn’t last very long at my house. When my uncle brought it over before driving North, he let me know that his trip wasn’t simply a ten-week assignment. He was going to be gone indefinitely. For better or worse, the snake was now mine. Not quite what I envisioned my first serious pet to be. I’m more of a cat person. Snakes don’t purr, and, as far as I know, they don’t cuddle.

For the first two days, the snake remained coiled in its tank, motionless if you didn’t pay attention to the tongue. By the third night, I felt confident enough to turn off the aquarium light while I slept. If I could remember my dreams, I would briefly describe them. I can only describe the paranoia I felt as any small noise would wake me. Then I woke to a crash, only I wasn’t sure if it had happened in my dreams or in actuality. I walked to the light switch, flipped it on. The snake was standing upright. My face was frozen, just as I remembered the mouse’s face. I screamed for my mother who was asleep across the hall. She stumbled into my room and said one thing: Fuck.

My first inclination, as I had never touched a snake before, was to throw a towel on it and push the serpent back into the aquarium. The snake was stronger than I was. The tiny piece of the snake’s tail grasped the top of the aquarium with more force in a half inch than I had in my entire body. I could only imagine the paralyzed mouse being suffocated and snapped in half, the snake’s dislocated jaw as it consumed the mouse, and its death.

After a struggle that could have been hours for however many minutes it actually took, the snake was locked up in the aquarium, and I was wide awake until we got the beast out of the house days later. My other uncle decided to take it off our hands.

We never heard from the snake again, as snakes haven’t discovered social media or (I hope) Google.

Since then, I’ve only kept furry pets in my home, found more reliable ways to discover new music, and have changed my definition of cool at least twenty times. ◥