Words by Stephanie Finger

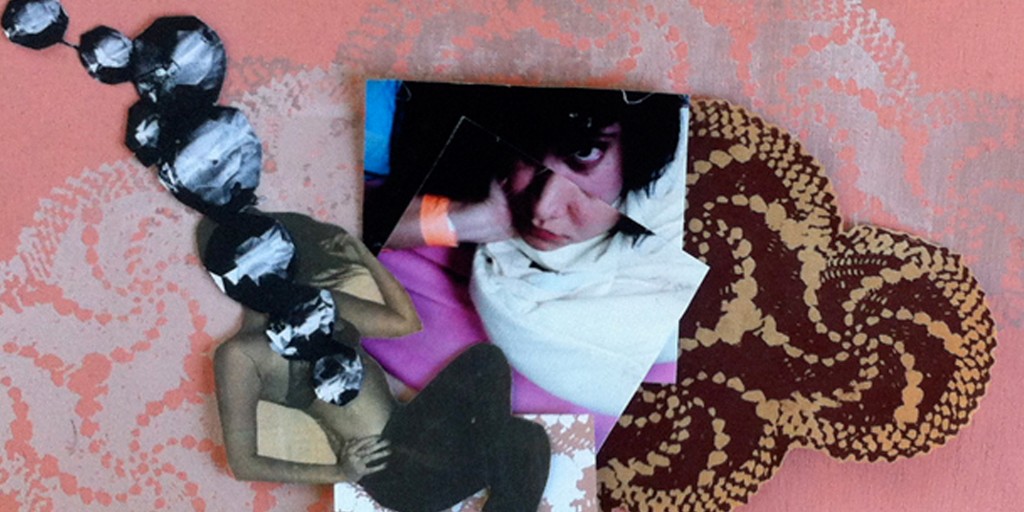

Image by Joan Zamora

His bedroom was, for the most part, bare; just a twin mattress tucked in the far right corner, loosely draped in a thin white sheet. The kitchen seemed similarly unused: cabinets strewn with mismatched Tupperware tops and bottoms, a bag of marshmallows, a carton of cigarettes. At dawn, when the sun crept through his curtainless window, the coins glinted with silver and coppery light, a stark contrast to the graying plaster walls and cardboard boxes layered thick with dust.

Uncle Edwin lived in Barton Creek Assisted Living, where he covered the floor of his room corner-to-corner with towers of coins, save narrow pathways to his bed and toilet. The result was majestic – a glimmering miniature city in an otherwise colorless place. I pictured Edwin’s thick fingers, nails cut to the quick, meticulously stacking the pennies so their ridges lined up. His condition mandated this kind of precision.

*

That was 2007. Edwin and I were both in Austin then. He worked the night shift bagging groceries at a 24 hour HEB, leaving time for coin castles by day. I was a freshman at The University of Texas, cooped up in the 24 hour library. We never crossed paths. When I sat next to him at Thanksgiving that year he asked if I’d ever seen him biking down Chicon on his way to work. It would be two years before gentrification took me that far east. Edwin was back in Houston by then, and I hadn’t seen him in months, maybe a year. I thought of him fondly on my way to dive bars on his side of town.

*

This year, Edwin, while bending down to feed his turtles, would collapse into his bathtub, Grandpa discovering him early the next morning, water still running, turtles clustered on the opposite side of the porcelain tub.

*

As kids, Dad and Edwin used to board their bedroom dresser like a fishing vessel. Dad balanced his soft, bare feet on the drawer knobs, pulling his little body to the top. If his pajama leg got caught on a corner – which happened now and again – Edwin was beneath him ready to break his fall. Edwin would toss Dad the necessary provisions from below: makeshift sea rods, nets and fish traps, bait they’d gathered from Grandma’s cupboard. Dad emptied the top drawer of clean white t-shirts and underpants to store their supplies. “Alright! Ready?” he asked, reaching down to lend Edwin a hand. Edwin staggered up the drawers and plopped beside him atop the dresser, his clumsiness causing the boat to rattle.

“Whoa! We nearly tipped,” he said, his marble eyes widening under his tousled hair.

“We’re still docked,” dad replied with a suggestive nod of the head.

Taking his cue, Edwin unraveled the imaginary knot and off they went: out to sea for hours on end.

*

With age, Edwin’s blue eyes dulled. His pure white skin went pocked and sallow, and his helmet of wild black hair became wispy strands, grey and thin like spider webs. Most imaginations dim with age, but Edwin never grew out of his. It seemed his physical appearance disintegrated as his imagination sharpened and took hold. The older he became, the more vivid his visions. By then, dad was play-fishing with us – his kids – not his middle-aged, mentally ill, little brother.

*

After finding Edwin, folded over the edge of the bathtub, phones began to ring. Each time the news broke, worlds slowed and paused. That afternoon, when mom called, I was wrapped in a towel rummaging through an empty refrigerator. I heard my sister’s voice soften to a whisper. “Whhhat?” It was an “h” heavy exclamation, followed by all the expected “Oh! Oh, my G-d! Awful! Just so…” Her voice trailed off. And then, “How’s Dad?”

*

Dad said when someone so close to you dies, for a time, your world does truly stop. Nothing exists but their absence. He noted, walking out of Edwin’s home that day, the neighbor cleaning his garage, a man crossing the street with a load of laundry, a family pulling up to KFC across the way. He was relieved to see the world carrying on.

*

Edwin’s illness was never named. I assume, buried deep in Grandma’s files, there’s a diagnosis that reads, “Mild schizophrenia with obsessive compulsive tendencies,” followed by a list of prescribed medicines and treatments, but we never labeled Edwin’s peculiarities. Even in the 60’s when Martin Luther King said things like, “There is a schizophrenia… within all of us… a tension at the heart of human nature,” Grandma & Grandpa were acutely aware of the stigma, and as acutely unaware of how to help their son.

*

Just a few days after Edwin’s death, we’d welcome Rabbi Morgan – a squat, middle aged man with pasty skin and a darting eyes – into my atheist grandmother’s home. Rabbi Morgan, though donning a Kepah and pleated suit pants, seemed more like a web-developer than a theologian. He sat at the head of the dining room table, dulled pencil in hand.

“Tell me about Edwin,” His eyes moved around the table, one-by-one soliciting our responses.

Grandpa answered by rattling off question about logistical details. “How long do these things usually run?’ ‘How many people can the temple accommodate?’ ‘A lot of people plan to attend.’ ‘Will family sit on the pulpit?’” Deciding on a time and place was the only manageable thing about losing your son.

Dad started with the basics: Where he lived: Montrose. Where he worked: Specs Liquor Store. His hobbies: shopping, collecting, records, women. We showed him all of Edwin’s watches, lined up in rows on the marble island, under a shelf that neatly displayed his comprehensive PEZ collection. There were 32 watches in total: digital, analog, silver, gold, plastic, some with calculator functions, and one that looked like a small TV screen. Looking down into the ticking watch faces, the beginnings of tears sprung in Dad’s eyes. Mom cringed with discomfort and Grandma sat her sadness on an elbow, sipping her martini as she stared out the window. “Did we decide on a timeframe?” Grandpa asked.

*

When the Rabbi’s eyes signaled it was my turn to tell him about Edwin, my aunt preemptively said, “He wasn’t close to his nieces,” and technically she was right. He wasn’t a regular at family functions and we never visited his “town home” (our euphemism for his room at the assisted living facility). When he did come around, we didn’t hug hello or goodbye, but I always took the seat beside him. The pungent smell of stale cigarettes didn’t interfere with my appetite like it did Mom’s, and I didn’t laugh uncomfortably or force a change of subject during the manic monologues about a new addition to his knife collection.

I never thought much of what we shared while Edwin was here, despite being sharply attune to it as we sat – hair disheveled, shirts half-tucked – among our manicured and shaven family at dinner. Grandpa told me once that he loved me for lots of reasons, but especially how I’d stayed more or less the same since childhood. Though the corners of my eyes crease now when I smile. Edwin was like that too. He brought my waifish, socialite grandmother (whose martini order I’d memorized by age eight), a super-sized bag of peanut M&Ms for her 60th birthday at the Omni Hotel ballroom. And once he very loudly, but so politely, asked Mom if he could smoke an electronic cigarette at Passover Seder, insisting the smoke was “Just water vapor! Scentless and hazard free!” like it was a new toy he couldn’t wait to show off. When she said no, he escaped to the backyard, where he removed half a Marlboro Light from his shirt pocket. Inhaling, his shoulders relaxed.

*

Dad says we all live lives that are both plainly mundane & extraordinarily unique. Maybe I felt Edwin and I shared that. I see now, that I was wrong. Edwin’s uniqueness was so complete it subsumed the mundane. He turned cold tile floors into glimmering cities of copper. ◥

Leave a reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.