Kingdom of Bones

by Miles Klee

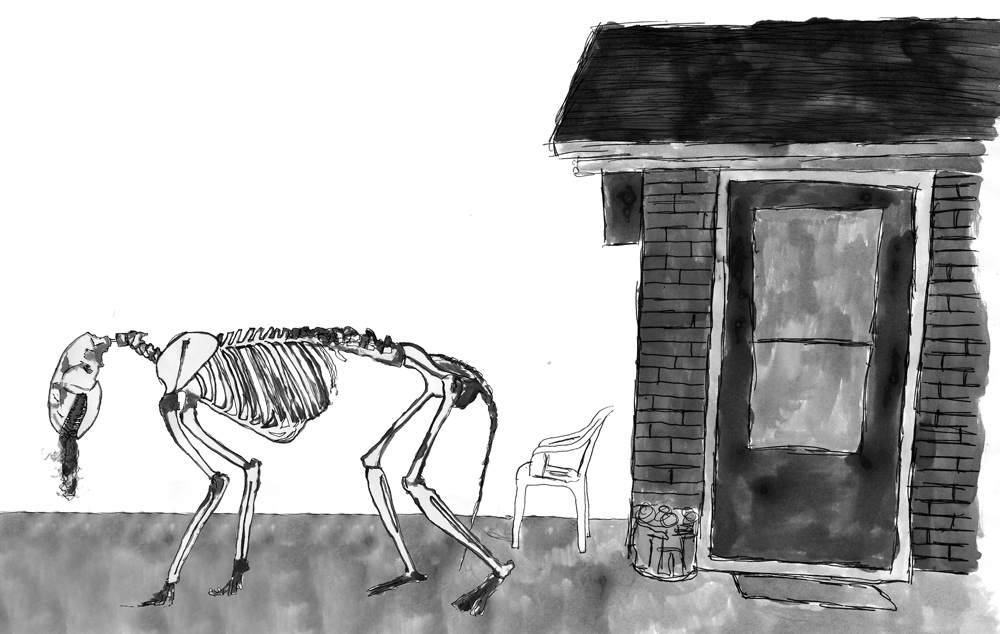

illustration by William Fatzinger, Jr.

I don’t visit museums of art, for reasons you’ll understand, and when I do go to other, mostly historical museums, it’s with the hope of finding a room that has no people in it. When that proves impossible, I find somewhere pleasant to sit for a very long time. I lived in Manhattan some months, not far from the American Museum of Natural History, and even a stroll to “get some fresh air” would lead me to its great stone steps, and thence into its echoing depths. On occasions when the museum became quite crowded, for example a Sunday in mid-December, I made my way to the Bernard Family Hall of North American Mammals. It’s there that you can study, in a splendid diorama, two stuffed but darkly alive mountain lions. There’s a polished wood bench a few feet away from the glass, and nobody has the time to sit there—nobody but me.

To pause at this spot allows one a painted view of scorched pink desert, with geologic blues and greens etched horizontal in distant buttes, a view that I want to say is of Utah, though I’ve never been to Utah, or to the southwest at all, for that matter. You see all this, the burnt landscape, from deep within the shade of a cave. One of the cats is crouched near the mouth, as if having heard a telltale noise, or assessing the sunset by how it fires the rock. The second cat, lying on its left side, looks in from an outer ledge, squinting with malice as it curls an outstretched paw … yes, like an insult, or some vulgar come-on. The cats are part of the nothing they inhabit—kings of it—their lair is full of stones and bones and both are leached of color, probably made of the same ceramic junk, synonymous that way—and the cats rule over this kingdom of bones. The phrase is so fixed in my mind that I almost have to say it aloud. (I say it aloud. No one hears.) The cats are rulers of what? The bones. What are bones? They’re nothing. And that is good enough, the cats appear to believe. But what sort of bones do we mean: Is that a human spine, lying there? A human spinal cord scattered among the animal bones of the cave, leftover piece of a skeleton model that has outlived its use. Now it’s a bit of window dressing, there in the Bernard Family Hall of North American Mammals.

Kingdom of bones, I whisper when I think of the people I killed in the art gallery. This is a dangerous habit, as it reminds me that the mountain lion exhibit—the flat, artificial vista, along with the cats themselves—amounts to a most deceptive, damning sort of art, the kind that has you wondering if it might move, a bit like a Cézanne painting, and once we’ve mentioned Cézanne we may as well shut up. Anyway, as with Cézanne, the scene is fraudulently simple, any dolt might try to recreate it, and yet you notice when any dolt does, the counterfeit’s unmistakable. We haven’t a clue what expert touch of a painter, nor taxidermist, sings these images to life. We only say I could have done that to annihilate a mystery. What I prefer to do when I locate some part of the museum where I am truly alone, or what I always think to do, is photograph the emptiness, or bottle the air, that empty museum air, but that would be quite foolish. You’re never quite alone by the mountain lions: there’s a family with a stroller, or a clique of pretty foreign girls, willing to spend a moment nearby. I’ve found, in fact, that beautiful women are somehow more likely than most to stop and admire the mountain lions, one vigilant, one impertinent, both utterly real, arranged in a tableau we are meant to consider stirring and correct. But what was I doing, looking at these cats, which were clearly art, which I cannot abide? They bask in the lost afterglow of a kill, awaiting the hunger of the next, only too pleased with themselves, what they own, which is nothing, so who cares. The cat lying down looks very bored. The shoulder muscles of the upright cat are all preparedness, mid-twitch and vascular, primed by the heat of late afternoon in the canyons, the endless waste of blasted nothing earth. Kingdom of bones, I say again.

I’m stupid from thinking of the million things I want, I think. I want to step outside with this pretty foreign woman, standing here at the mountain lions, walk around in the snow with her, then take her inside and spy a few white specks left melting in her hair. I want to kiss the melting snow in her hair. Then I would tell her that I’m a murderer, a terrorist, and she would not understand me: her English is not so good. I don’t mind. I don’t mind, either, that she’ll not understand my peculiar need to stay there with the mountain lions, and not go farther into the Bernard Family Hall of North American Mammals—though by the way, just who the hell are the Bernards, and why are they so keen on the mammals of North America? It’s the sort of thing you can’t bear to look up, simply because you can’t bear to be that interested. I am not even sure how I know that that is the family for whom the wing is named, nor that I know any family called the Bernards. I have a feeling that if I lived next door to the Bernards, I would burn their house to the ground. Clearly that is my failing, not theirs, and yet I’m certain the Bernards would understand. If they’re funding goddamn museum wings, I mean.

I don’t want to get angry, it’s stupid, and I get angriest about being angry, being unable to control my anger, it makes me weak and hollow. This almost never happens, so when it does, I’m even angrier, I want to kick someone’s head in. In England, at school, I wrote an art history essay about a famous old building, there in the center of campus, a structure that I argued was radical and fluid, a quiet subversion of the neoclassical style it appeared to totally inhabit. The professor gave me an average, insulting grade, finally concluding that I’d been reading too much Nietzsche. The building, he scolded in hasty, almost illegible notes, was a model of architectural harmony, completely without the dialectic struggles and paradoxes I had identified. That opinion I could have swallowed, however brainless it was, but I couldn’t let the gratuitous mention of Nietzsche, whom I’d never read and never will, just hang there. I approached the professor in a small café and smacked one of England’s pale, slimy sandwiches out of his hand. He was shrinking and terrified as I screamed continuously in his face. Nietzsche, I began. How dare you invoke Nietzsche, you fraud. I said the name “Nietzsche” so many times, and so insanely, that I must have pronounced it several ways, none of which sounded right. Who but Nietzsche himself could be sure? I didn’t imagine I’d have to say “Nietzsche” aloud, and in such unusual circumstances. Police dragged me off. I was expelled. The professor took a sabbatical in Switzerland, to write a book about something else he pretended to understand. Nietzsche! I should have slit his throat in that café, in front of everyone.

The effect of Nietzche’s name on that paper was like that of one’s own, at least when it has been pointlessly spoken—my name, whenever it enters the atmosphere, always seems unnecessary and odd. For years I had neighbors who would find occasion to address me as William, even in passing, and soon it felt as though they were challenging me to remember their names, which of course I had no intention of doing. All the same, their insistence on calling me by name while waving from their driveway, or brushing by in a crosswalk at lunchtime, drove me to seek out their names once more, that I might throw them back in their faces. I wouldn’t ask them; I could not give them that smug pleasure. Instead I woke before dawn one Saturday in winter, stole across their snowy front yard and into their unlocked home in order to study the mail in the foyer. But after I learned the neighbors’ names, the moment to use them never came. They went on addressing me as William, and I kept rehearsing their names in my head, the way I would one day say them, surprising even myself. Eventually, they moved away—I found out when I saw them packing up one morning. “It’s been nice, William,” said the wife as she got into the car. “William, see you later,” the horrible husband smiled. “Goodbye,” I said. “Whoever you are.” Did they hear me? I doubt if they wanted to. When you say something truly unacceptable, people pretend they didn’t hear it. They give you a chance to correct yourself without losing face. But the neighbors didn’t bother with that, they got into the car and left. It was like they really hadn’t heard.

If my plan to kill those people at the art gallery came at all close to unraveling, it was four days before, at Lake Sangepour, in Stonefield, one town over. I couldn’t store the sarin canister in my grandmother’s house, which I had inherited, for fear it would go off and kill me while I slept. I kept it buried by a spruce tree at the south end of the lake, where the hikers didn’t bother to go, since the view wasn’t nearly as good. Nevertheless, each afternoon, I convinced myself the sarin would be found, and raced to the spot to dig it up, then bury it somewhere else. I was digging on this near-final occasion, careful not to jab the ground in a way that might damage the canister, and had just scraped shovel across familiar metal when voices flowered somewhere behind me. Father and son, I could tell, and soon they were there in life jackets, holding a yellow kayak between them, the boy no more than thirteen. “Howdy,” the father said. “Treasure hunt?” “I’m burying my cat,” I replied. I had a handgun in my waistband, a hunting knife in my boot, a Taser in my shirt pocket. Why had I mentioned a cat? I didn’t know anything about cats. Cats were probably cremated. “Sorry for your loss,” the boy said. The dad squeezed his shoulder approvingly but in the end said nothing. They set the kayak down and got in and began to glide out, the paddles making no noise. Lucky they hadn’t stayed longer. Lucky for them, and lucky for me. How horribly lucky we were.

But what has any of this to do with my days in museums? First, let me tell you about my wife, Simone, whom I met in France, not long after my sarin attack, at the Musée Matisse, in the 17th-century Villa des Arènes. Well, forget the museum a moment: that night we tried to go to a casino. They wouldn’t let us in because I was wearing sandals. She found that hysterically funny. We wandered into the old part of Nice, the narrow alleys and shitty tourist shops. She wanted to browse a jewelry stall, and while I was waiting outside I scanned the rickety table of an old bookseller. He spoke to another elderly man while I studied his merchandise, and half a year in France must have helped my ear, because at once I knew what they were saying. The bookseller, stooped and spotted, was asking his even older friend, who walked with a cane, to watch his table while he went to fetch something. When he left, the man with the cane glared at me, fully prepared to punish any thieving sleight of hand. There was nothing on the table I wanted—nothing of any value, in fact—and so I was soon possessed by thoughts of attacking the suspicious old man, beating him with his heavy cane, teaching him that he had no right to imagine his own strength. Could he stop me stealing these books? He could not. Could he stop me taking his life? He might not even try. But Simone came out of the jeweler’s, wearing a bright coral necklace, and all else rushed out of my mind.

“I wish there were a museum museum,” Simone sometimes likes to say. “About our tendency, once we get a bit of knowledge, to arrange it all nicely and stroll about inside it every now and then. ‘People of this period,’ the people of the future will say, ‘did not create further history, but reflected on what had happened so far, fragments of it arranged carefully under glass. They dug up the past and stared in awe, because a single image surfaced repeatedly: a man cheating you with a dirty wink as another snuck up in a painted mask to stab him in the neck.’ You can’t trust a human,” she’d add, “no matter how wonderfully they express their displeasure at having to play the same game as you—it is distraction. They want to win themselves.” I look at my dog, snoozing peacefully on the couch: here have we so much in common and none. Moxie, the dog, doesn’t know or care what I’ve done. Simone doesn’t know, but she’d care. If you asked me why I killed those people, I would have to say to mind your own business, and beyond that I can only blame the kingdom of bones, which is not itself subject to explanation, but might be described as the distance between what is and what might, such that what is can’t bear observation. The kingdom of bones is an all-connecting absence, a Horla, a pause in one’s heart as all the world goes on. Lately, I must say, there is something wrong with the weather. Not to say the weather is bad, or even unusual for the season, though it has been rather windy some days. It’s just wrong, simply wrong. Weather that arrives out of spite—exactly! Arrives, as if weather comes from someplace else. Truthfully, much of it does: on our screen, we see the storms and cold fronts move in like armies across the nation. But then where does the weather begin? Don’t give me that butterfly shit, I’m asking: Where does weather begin?

Thirteen is not that many. Only a dozen, depending who counts. A dozen at least deserved to die; the Swede is the death I regret. The two curatorial employees, the pair of security guards, the couples on a double date, the three art critics and the wealthy patron, they had no business sharing the same air as that painting—but the Swede, whose name was Axel Persson, a middle-aged tourist traveling alone. Who friends would later say was not much for the arts, more an outdoorsy, hiking type. Who had strolled in almost at random, with just twelve other people there and all of them out of inflexible obligation. Wandered in for the experience, it seemed, was the only one there in absolute good faith, for good reason, which is to say no reason at all. Perhaps he had a dread of some other place, and came seeking refuge, someplace empty in which to be alone, in which nothing mattered and nothing was expected. Perhaps I gave it to him.

“Kingdom of Bones” is excerpted from the upcoming novel “The Gulf.”

Miles Klee, a reporter for the Daily Dot, wrote the novel “Ivyland,” a finalist in the 2013 Tournament of Books, and “True False,” a forthcoming collection of stories. His essays, satire, and fiction have appeared in The Awl, 3:AM, Lapham’s Quarterly, Vanity Fair, The Collagist, McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, Pinball, Salon, Contrary, Unstuck, Birkensnake, The White Review, andelsewhere. He lives in Manhattan’s Morningside Heights.

William Fatzinger Jr. writes stories and draws drawings. He has been a convenience store clerk, a darkroom chemist, an apprentice to a telescope maker—he has shoveled sand for fake indoor beaches on commercial photo shoots. He lives in Austin, Texas, with his wife and a eleven year-old albino frog named Zebulon Pike.